The land, the sea, and the heavens above

Geoff Manaugh at BLDGBLOG has written a terrific riff on historian John R. Gillis’s new book The Human Shore: Seacoasts In History. After a phrase from Steve Mentz, it’s called “Fewer Gardens, More Shipwrecks”:

“Even today,” Gillis claims, “we barely acknowledge the 95 percent of human history that took place before the rise of agricultural civilization.” That is, 95 percent of human history spent migrating both over land and over water, including the use of early but sophisticated means of marine transportation that proved resistant to archaeological preservation. For every lost village or forgotten house, rediscovered beneath a quiet meadow, there are a thousand ancient shipwrecks we don’t even know we should be looking for…

We are more likely, Gillis and Mentz imply, to be the outcast descendants of sunken ships and abandoned expeditions than we are the landed heirs of well-tended garden plots.

Seen this way, even if only for the purpose of a thought experiment, human history becomes a story of the storm, the wreck, the crash—the distant island, the unseen reef, the undertow—not the farm or even the garden, which would come to resemble merely a temporary domestic twist in this much more ancient human engagement with the sea.

The Hebrew Bible famously begins human history with a garden, followed by agriculture, then a flood, then cities, then wandering in exodus — but that story’s probably completely inverted. (The fact that the story’s written in a script likely borrowed by seafaring merchants is a tell.)

Even after agricultural urban civilization settles in, there are continued raids from “sea peoples”, Vikings, Mongols, and the British Empire — wanderers over land and sea who periodically crash into the farmers’ cities and make them their own, through trade and/or plunder.

Robert Graves thought all Greek mythology (and maybe all mythologies) dramatized the conflict between new and old gods, particularly the matriarchal gods of agriculture with the patriarchal gods of the sky and sea. In all the stories, he thought, you could find a trace of the suppressed gods, a counter-narrative that was never completely erased.

Here, too, we get our opposing views of nature: the regular, settled rhythms of Hades and Demeter, and the inhuman danger of Zeus and Poseidon — Walden vs. Moby-Dick.

Maybe the most successful myths are the ones that reconcile the two strands, legitimizing the victorious shipwrecked wanderers by explaining that the gardens they conquered were always theirs to begin with — that they had brought civilization and enlightenment to the farmers, whose songs their children sung, without knowing where they had come from.

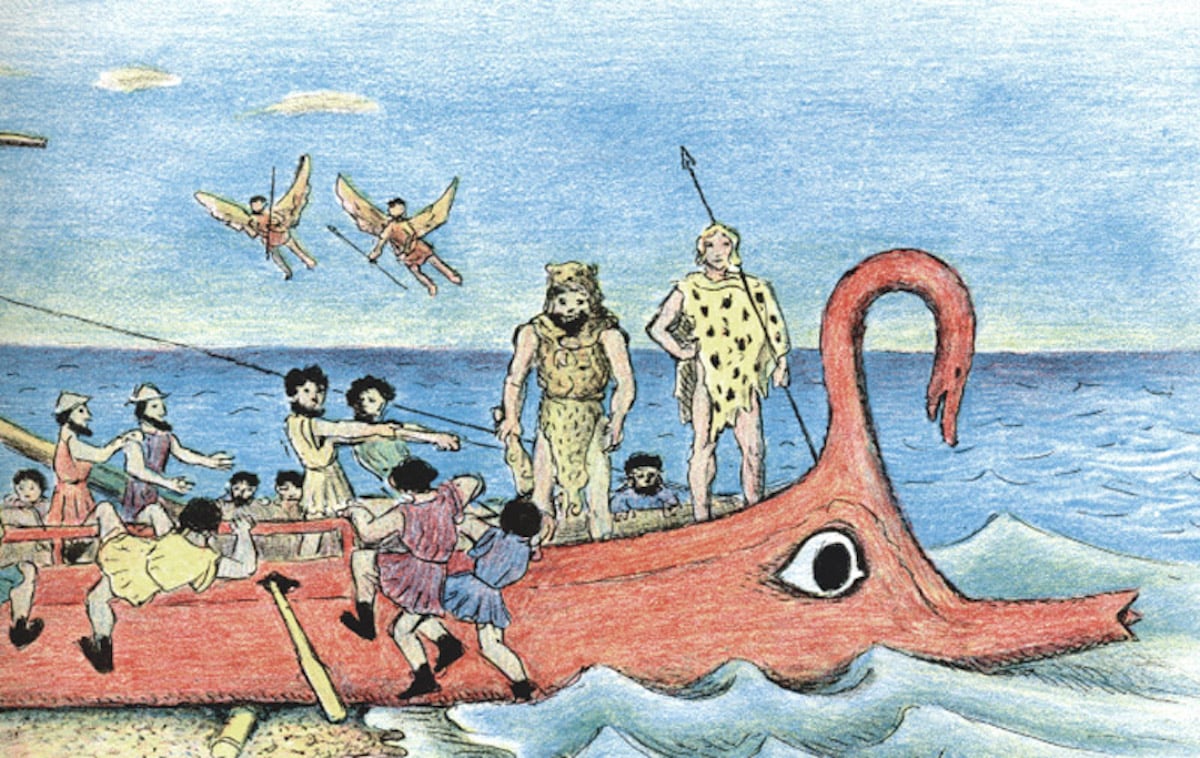

(Top image from D’aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths)

Stay Connected